The State of the Rhino: World Rhino Day

/First published 18/9/18, updated annually

What’s the state of the Rhino? World Rhino Day is celebrated on September 22nd every year, enabling cause-related organisations such as The International Rhino Federation to raise awareness of the plight of the rhino and highlight its issues. #WorldRhinoDay #TeamRhino

World Rhino Day was first announced by WWF-South Africa in 2010, growing in 2011 into an international success, encompassing both African and Asian Rhino species, and uniting concerned organisations, businesses and individuals from all around the world.

Rhinos are poached for their horn. Rhinoceros horns are used for dagger handles in Yemen and Oman, and in traditional medicines in parts of Asia, despite China signing the CITES treaty (1993) which had declared trade in rhino horn illegal since 1977, and removing rhino horn from the Chinese medicine pharmacopeia, administered by the Ministry of Health. Vietnam reportedly has the biggest number of rhino horn consumers where an average-sized horn can bring in as much as a quarter of a million dollars.

The rhino poaching crisis began in Zimbabwe, facilitated by the difficult socio-economic and political climate, but soon turned to South Africa, the country hit hardest as it holds nearly 80% of the world’s rhinos.

The South Africa poaching crisis began in 2007, with 9000% increase in rhino poaching 2007-2014 and more than 1000 rhinos killed each year 2013-2017 to a peak of 1,349 in 2015: 90% of African rhinos poached are in South Africa, and around 50% are poached in Kruger National Park. Around 2013, the poaching crisis extended to other countries such as Kenya and Namibia (Save The Rhino). In the 2010-2020 decade, 9,442 African rhinos were lost to poaching.

Reducing Rhino Poaching

Sadly SouthAfrica's battle to defeat #rhino #poaching took a turn for the worse in 2023 with the 499 rhinos hunted, an increase of 51 from 2022.

But generally there was a decrease in the rate of poaching across Africa in the 5 years 2017-2022, with 2,707 rhinos poached. This may demonstrate that anti-poaching work having an effect, or that with significantly fewer rhinos surviving in the wild, it is getting harder for poachers to locate their prey, plus the impacts of Covid-19 lockdowns, reducing poaching rates from 3.9% of the population in 2018 to 2.3% in 2021 (IRF, 2022). Sadly, with Covid restrictions lifted, but worsening economic challenges for anti-poaching and poachers alike, poaching was on the rise again driven by illegal trade of horn of approximately 1000/year (IRF, 2022)

State and private rhino owners are increasingly dehorning rhinos to deter poachers, or poisoning or colour-dying horns safely for rhinos to reduce human consumer demand.

While poaching is often the most visible and understood part of wildlife crime, the transport, trade and sale of illegal rhino horn – from a protected area, across provincial boundaries and national borders to the end consumer – requires law enforcement coordination between countries vital to breaking the hold of international criminal syndicates. As a deterrent, in Vietnam, authorities have worked to secure longer sentences for wildlife criminals, and local communities generally need to be included as active participants in wildlife conservation and receive economic incentives that improve livelihoods.

Other impacts on Rhinos

Adult rhinoceroses have no real predators in the wild, other than humans. Young rhinos sometimes fall prey to big cats, crocodiles, African wild dogs, and hyenas.

But changing climate situations are impacting rhinos through habitat and extreme weather. Drought leads to loss of much needed water for rhinos, more wildfires impacting habitat, and loss of farming for humans’ much needed income - luring them into poaching. And floods can mean an increase in invasive plant species crowding out rhino food plants, as well as direct drowning, or separation of mothers and young.

Thankfully rhino conservation has seen success. In 2007, roughly 20-21,000 rhinos roamed Earth. Today, rhino numbers are estimated at 27,000 (IUCN African Rhino Specialist Group, AfRSG, 2023) – an increase of nearly 30%, but again decreasing.

Did you know… Rhinos are called ‘bulls’ (males), ‘cows’ (females) and calves?

The State of the Rhino 2023 (International Rhino Foundation)

Poaching still threatens all five rhino species and has increased in several regions that had not previously been targeted.

27,000: The number of rhinos left in the world with all five species combined.(AfRSG)

Declining: White rhino. South Africa continues to battle devastating poaching losses as poachers target reserves in KwaZulu-Natal province. But 2,000 white rhinos from “World’s Largest Rhino Farm” will now be rewilded throughout Africa. Amazingly, Southern white rhino populations have increased for the first time since 2012, rising from 15,942 at the end of 2021 to 16,803.

Declining?: Signs of Sumatran rhinos are increasingly hard to find, creating more uncertainty about their population in the wild.

Increasing: Black rhino, despite constant poaching pressure.

Increasing: The greater one-horned rhino population in India and Nepal thanks to strong protection, wildlife crime law enforcement and habitat expansion.

Unknown: The status and whereabouts of 12 of the approximately 76 remaining Javan rhinos.

Climate change, as well as poaching and habitat loss, is increasingly impacting many facets of rhino survival.

The Rhino Species

There are 5 species of Rhino, full name Rhinoceros, in the odd-toed ungulate family Rhinocerotidae.

Two species are native to Africa: the Black Rhino (Diceros bicornis) and the White Rhino (Ceratotherium simum).

Three species are native to Southern Asia: the Great One Horned Rhino, also known as Indian Rhino (Rhinoceros unicornis), native to India and Nepal, the Javan Rhino (Rhinoceros sondaicus) found in Java Island, Indonesia and Vietnam, and the Sumatran Rhino (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) also known as the Hairy Rhino, native in Sumatra Island Indonesia, Southern China, Bhutan, Cambodia and Borneo.

The White Rhino - The “Square-Lipped” Rhino: Population 16,803 in 11 Contries in Africa - Decreasing (IUCN/IRF, 2023)

IUCN Red List Classification: Near Threatened

The Northern White Rhino

The northern white rhino is a subspecies of white rhino, which used to range over parts of Uganda, Chad, Sudan, the Central African Republic, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Years of widespread poaching and civil war in their home range devastated the populations. By the time expert trackers determined that they were extinct in the wild in 2009, only a handful of zoo animals remained, none capable of breeding. In 2018, the death of Sudan, the last male Northern White Rhino, a member of a functionally-extinct subspecies of White Rhino, left only two females: his daughter and his granddaughter.

To try to preserve the species, genetic material was collected from Sudan before he was euthanised for yet-unproven costly and complicated procedures using advanced reproductive technologies including stem cell technology, artificial insemination and IVF with eggs from southern white rhino females in European zoos, so that his death will not signal the end of the species.

The northern white rhino females cannot mate with a black rhino, but could mate with a southern white rhino, which are not endangered though a different subspecies genetically. The offspring would not be 100% northern white rhino, but experts believe it would be better than nothing.

Sadly though, neither of Sudan’s female relatives, Najin and Fatu, were able to carry a pregnancy, but a groundbreaking procedure carried out by Ol Pejeta Conservancy and partners in August 2019 meant they still could mother the next generation of northern white rhinos: 5 eggs were harvested from each of the females in an operation that has never been attempted in this species before, of which 7 (4 from Fatu and 3 from Najin) were successfully matured and artificially inseminated through ICSI (Intra Cytoplasm Sperm Injection) with frozen sperm from two different deceased northern white rhino bulls, Suni and Saut, on August 25th 2019. In September 2019 it was announced that two northern white rhino embryos had been successfully matured and fertilised: both using eggs from Fatu, the youngest of the two northern white rhinos, and frozen sperm from Suni a deceased northern white rhino male.

These first ever successfully matured and fertilised in-vitro embryos, were frozen in liquid nitrogen to be later transferred to a southern white rhino surrogate mother. (One of 6 potential surrogate mothers, Victoria, already gave birth following successful innovative artificial insemination in July to a Southern White Rhino at San Diego Zoo, California). In 2020 this work was held up by the impacts of Covid19, but resumed in 2021 with the creation of additional embryos, using semen from deceased northern white rhino bull Angalifu, bringing the total to 22.

The Southern White Rhino

For Southern White Rhino, births barely outstrip deaths, due to being a poaching target. That said, the Government of South Africa and dedicated conservationists teamed up to bring the southern white rhino back from fewer than 100 individuals in the early 1900s, to more than 21,000 at the end of 2012, but since then, white rhino numbers have decreased by 20% - though risen in 2023 by 5%.

The sale of the Platinum Rhino Project and their 2,000 southern white rhinos - 1/8 of the white rhino population - to nonprofit African Parks, will begin historic and critical translocations across Africa in order to build rhino populations and conservation in key protected areas.

The Black Rhino - The “Hook-Lipped Rhino”: Population 6,487 in 12 Countries in Africa - Increasing (IUCN/IRF, 2023)

IUCN Red List Classification: Critically Endangered.

By 1993, less than 2,300 rhinos remained from as many as 100,000 throughout Africa in 1960, poached down to 65,000 by 1970 (IRF, 2023). Now, black rhinos number over 6,000 animals, with an encouraging increase of 12%, 2017-2022, and +5% in 2023.

There are three subspecies of black rhino: the southeastern, eastern and southwestern. All subspecies’ populations have grown, with the largest gains seen by the eastern black rhino (33-42%) over the past decade. The most numerous subspecies is the southwestern, moving from Vulnerable to Near Threatened due to its sustained population growth over the last three generations, while the other two subspecies and the species as a whole remain classified as Critically Endangered.

The largest population of black rhinos in Africa is in Namibia, a stronghold for the southwestern subspecies, with approximately 90% of the total population. Alongside the poaching crisis, major droughts between 2017 and 2019 meant proactive population management and translocations for water and safety were essential for the survival of rhinos. In Namibia, Etosha National Park holds the world’s single largest black rhino population, with rhino numbers steadily increasing thanks to a well-established conservation management programme.

South Africa accounts for about half of the total black rhino population (2056), historically seeing most poaching at Kruger National Park, now shifting to other provinces, such as KwaZulu-Natal.

In Kenya, faced with the poaching crisis, a collaborative strategy placed remaining black rhinos into relatively small, intensively protected fenced sanctuaries on government and private land, and all black rhinos under state ownership: private and community conservancies may apply to the Kenya Wildlife Service to become black rhino ‘guardians.’ Their Black Rhino Action Plan every five years achieved their goal of a population of 830 black rhinos by the end of 2021. 2020 saw their first zero-poaching year in 21 years.

Black rhinos have also been returned via translocations to previous poaching-crisis Zimbabwe, with several births and reducing poaching from 77 individuals in 2019 to 10 in 2021, for the first time in over 3 decades, Zimbabwe has surpassed 1,000 rhinos: 616 black and 417 white rhinos.

The Greater One-Horned or Indian Rhino: Population: 4,018 in 3 Countries - Increasing

IUCN Red List Classification: Vulnerable

Thanks to strict protection by government authorities in India, Bhutan and Nepal who work together to implement a trans-boundary management strategy (such as protection by military conscripts and habitat management), the population has rebounded from fewer than 100 individuals in the early 1900s to more than 4,000, though still vulnerable.

Poaching remains a threat, but numbered just one individual in 2021, none in 2022, but two in 2023. The Indian Rhino Vision 2020 programme closed, but partners met in 2022 to put forward plans for the next stage in development (IRV 2.0).

The Javan Rhino: Population 64—76 in 1 Country: Stable

IUCN Red List Classification: Critically Endangered

There are no more than 68 animals found in Indonesia’s Ujung Kulon National Park (UKNP), where they are heavily protected, and under serious threat from potential eruptions of close-by Krakatoa, the volcano that devastated the region in 1883, and “Anak Krakatau,” or Son of Krakatoa, also active a short way away. In 1967, there were just 25 Javan rhino individuals, and in 2010 fewer than 50 in UKNP. Growth is slow. and increasing incursion attempts in 2023 alarming.

The Sumatran Rhino: Population 34-47 /<80 in 1 Country - Decreasing

IUCN Red List Classification: Critically Endangered

In existence longer than any other living mammal and considered “primitive”, the Sumatran Rhino in Indonesia is also known as the Hairy Rhino as it is the hairiest of all species especially on the ears and tail, and is by far the smallest species of rhino.

There are up to 4 isolated populations and as many as 10 subpopulations of Sumatran rhino left in Indonesia. But only one of these wild populations, in Gunung Lesuer, is believed to have enough individuals to be viable.

Due to hunting for its horn and forest habitat loss (much due to palm oil deforestation), the Sumatran Rhino is also the most in peril and possibly the most endangered large mammal on Earth. The government of Indonesia reports that there are no more than 80, but a recent report from Asian Rhino Specialist Group (AsRSG), African Rhino Specialist Group and TRAFFIC estimated the population at just 34-47. Because so few remain, and those surviving have moved into remote areas, they are difficult to track and uncertainty abounds.

Sumatran rhinos were declared extinct in the wild in Malaysia in 2015. Three small, isolated populations exist on Indonesia’s Sumatra Island, plus it is believed that fewer than 10 of the Bornean subspecies of rhino survive in small and highly fragmented populations in eastern and central Sabah, with similarly low numbers in Kalimantan, Indonesia. With such low numbers, in separate pockets, the threats to the species now include the low probability of fertile females and males meeting in the wild, ageing without reproducing, or inbreeding.

The Sumatran rhino is not just a unique species - it’s in its own genus, Dicerorhinus, separate from all other living rhino species. It means Sumatran rhinos’ behaviour, nutrition and reproductive physiology is different from other rhino species.

Known populations are heavily guarded by anti-poaching units, with a very real danger of becoming extinct soon without intervention.

How do you rescue a rhino population?

Plans are underway to safeguard and increase the Sumatran Rhino population: The government of Indonesia’s Sumatran Rhino Rescue is a huge, multi-stage, multi-year emergency action plan to save the Sumatran rhino, working with an alliance of international rhino conservation organizations including the International Rhino Foundation. The stepped program will:

Survey & Capture - gathering information on individual rhinos to determine their locations through camera traps, to capture them in pit traps - the best way in the dense Indonesian jungle, with soft muddy bottom to cushion a rhino’s fall, covered to camouflage, with veterinary teams, rangers, and transport staff on stand-by ready to act immediately to…

Translocate - From the pit traps, the rhinos are manoeuvred into crates to move the rhino to pre-determined locations by truck and even plane. With security and safety paramount, the new location may be initially a temporary ‘boma’ holding pen home to acclimatisation and monitoring medically, or to another permament (semi/)wild home, such as specialised breeding facilities .

To support the program, the Sumatran Rhino Sanctuary (SRS) now has three locations in Indonesia to accommodate rhinos rescued from surrounding areas and the offspring they produce. Between the 3 facilities, the Sumatran rhinos will be managed as a meta-population - one large breeding group - to increase the chances of successful births and strengthen the genetic diversity of the population over time. With a gestation of around 16 months, a female Sumatran rhino gives birth only every 3-4 years – it could take decades to rebuild the population to sustainable numbers.

Breed - In the history of Sumatran rhino captive management, only two facilities have been successful in breeding the species — the Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Gardens in the USA, and the Sumatran Rhino Sanctuary (SRS) in Way Kambas National Park, Indonesia - with only 5 Sumatran Rhinos born in captivity.

In May 2022, the Indonesian Institut Pertanian Bogor University (IPB University) and the German Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (Leibniz-IZW) signed a memorandum of understanding. The collaboration establishes “The Center for Assisted Reproductive Technologies and Biobank” at the IPB University to provide a state of the art laboratory, networking opportunities for scientists and others, and capacity building support in Indonesia for assisted reproduction techniques (ART) and biobank applications, particularly targeting Sumatran rhinos.

Reintroduction - returning rhinos to the wild depends on the success of the breeding program, continued protection programs (which will never stop), and habitat restoration projects. Reintroduction will likely happen slowly over years, and captive breeding will continue until there is sufficient evidence that wild populations are growing and thriving.

In Summary

Despite some successes, Rhinos are amongst the most endangered species on the world, requiring expensive round-the-clock guarding from the ever-present threat of poaching.

Work is also being done to stem demand for rhino horn and thus poaching, China and Vietnam being the top two consumer countries, and to intensify international pressure on country governments to enforce wildlife crime laws.

Rhino conservation initiatives and activities help create the funds to raise awareness for the plight, support the species guarded protection and invest in innovative scientific means of species conservation, to ensure these species don’t go extinct.

As The Last Northern White Rhino, the demise of Sudan, “the most prolific rhino ambassador in history”, is hoped to be seen as a seminal moment for conservation worldwide, to ensure this does not happen to any other Rhino species.

Act!

Thanks to The International Rhino Federation for the information, please support their Save The Rhino campaigns and join #TeamRhino this World Rhino Day

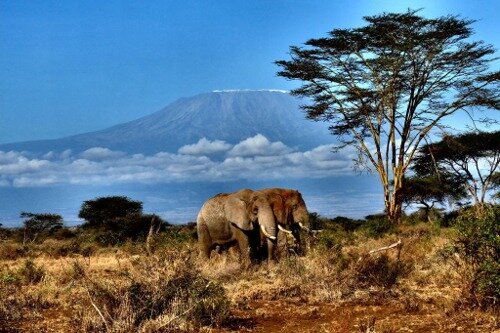

See for yourself: You may see Rhino in the wild with Earth Changers in Kenya.