How to Measure Tourism’s Impact? Part 3: Can Tourism Help Well-being, Social Progress & Living Standards?

/Does tourism help destinations, and how that can be measured? Economic growth alone is no longer enough. Society also needs to consider basic human needs and well-being. Where GDP might be a great tool for measuring economics, there is more to life than economics.

>> In Part 1, we asked why, and what’s wrong with tourism targeting quantity of visitors, not quality?

>> In Part 2, we considered whether tourism actually creates happiness, for hosts as well as guests, and how that can be measured ‘Beyond GDP’.

GDP does not demonstrate happiness, cultural resilience, or environmental health. Simon Kuznets, Nobel Prize-winning economist and designer of the modern GDP himself said in 1934,

“The welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measurement of national income.”

Even if GDP is growing, if a society doesn’t provide the circumstances to enable its people to meet basic needs and improve quality of life, it is not succeeding.

For example, some Middle Eastern countries demonstrate very high GDP, but social progress lags. Other countries may not have high levels of GDP, but do very well on social progress, such as New Zealand, whose Prime Minister foresaw “while economic growth is important… it alone does not guarantee improvements to our living standards” (Jacinda Ardern, 2019).

In fact, the pure pursuit of GDP can come at a cost to social well-being, as we see in overtourism costing communities dearly.

Measuring Social Progress

The Social Progress Index (SPI) is a first-of-its-kind tool that uses no economic indicators to measure what life is like for a population. Co-created by Harvard professor Michael Porter, it can help action social progress by highlighting areas of strengths and weakness and identifying priorities, and alongside GDP can demonstrate his concept of the ‘shared value’ of social value plus economic value (Deloitte, 2015).

It is used by 45 countries, states, regions, cities and even communities to guide support, impacting the lives of more than 2.4 billion people, for example:

• The European Commission’s US$100 billion Cohesion Strategy, to raise living standards in more deprived parts of the European Union.

• Indian corporations are using state and district data to target their charitable giving where they will have the greatest impact.

• In Brazil, multinational corporations like Natura are using customized indexes to ensure their supply chains are socially and environmentally sustainable.

It is the first comprehensive model to measure human development that does not include Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or other economic variables, but complements them. It is governed by four basic principles:

• it only considers social and environmental indicators;

• indicators are of outcomes not inputs;

• relevant indicators for context; and

• indicators may be the objective of public policies or social interventions.

and considers three dimensions, each composed of between three and five specific outcome indicators:

• Basic Human Needs, eg. personal safety, shelter, water and sanitation, nutrition and medical care

• Fundamentals of Wellbeing, eg. ecosystem sustainability, access to information and communication, health and wellness.

• Opportunities, eg. tolerance and inclusion, personal rights, access to advanced education, personal freedom and choice

The Social Progress Index aggregates data across 12 core areas in the three dimensions to create a single social progress score, providing a quick but thorough snapshot of overall progress toward the goals, and a comparable index between countries.

Social progress means striving for inclusive growth. Developing states may be helped by Foreign Direct Investment, to spur on to the next level of development, if invested in the right areas and if poverty traps and tax advantages are not a barrier to social progress. In this way, the SPI can help guide foreign investment.

It can also help policy-makers track and report in a practical and consistent way progress towards the SDGs, particularly for governments conducting their Voluntary National Reviews (VNRs).

Incredibly, all 5 Nordic countries of Europe figure in the top 10 of the global Social Progress Index (Norway, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Iceland), and most of Europe in the top 2 tiers.

The U.S., for example, the largest economy in the world, and in the top 10 for GDP (purchasing power parity) performs worse than expected in areas such as health and wellness, personal safety, and environmental quality.

By contrast, Costa Rica, with significantly lower GDP PPP per capita (about 28% of the U.S.) has a social progress score far closer to that of the U.S. and other more developed countries than to many of its economic peers. It scores higher than the U.S. for health and wellness, environmental quality and personal rights.

Here you can see the latest Global Social Progress Index.

Measuring Tourism through the Social Progress Index in Action

Costa Rica is the first country to apply the Social Progress Index to a major economic sector – tourism - to measure the effects of tourism on local communities.

In a concrete and precise way it measures the well-being of people in tourist destinations and creates benchmarks between territories, to assess and improve the sustainability of its destinations and serve as a guide for new tourism policies and public-private collaborations to create positive impacts for local communities.

This creates knowledge to inspire the participation of the local community and enables the creation of a roadmap of actions to strengthen the role of locals in the tourism sector as a catalyst for inclusive sustainable development and to meet the UN SDGs.

In doing so, Costa Rica has shown their 32 ‘tourism development centers’ have better social progress results than the cantons in which they are located. This validates the social and economic importance of tourism, as well as the possibilities of integral development that they present for their inhabitants, mainly in areas far from the centre of the country.

But critics point out the criteria are based on Western values, ignoring the Global South, and questioning incomplete and/or inaccurate data for environmental hazards, energy usage, specific health issues, employment availability and quality, income and gender inequalities, and corruption, and unlike the Happiness Index, that it ignores measures of subjective life satisfaction and psychological well-being.

Measuring Well-being and Living Standards

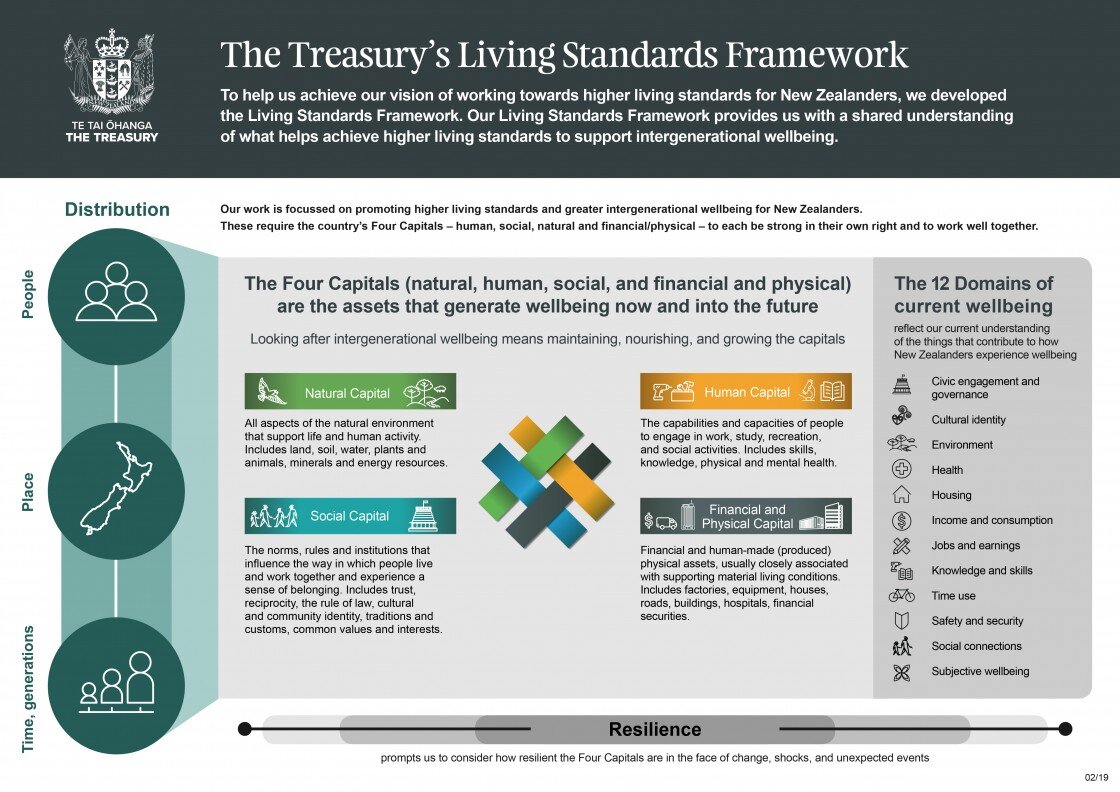

New Zealand has developed its own Living Standards Framework, the Treasury’s perspective on what matters for New Zealanders’ well-being, now and into the long-term future. It includes

• 12 Domains of current wellbeing outcomes: Civic engagement & Governance, Cultural Identity, Environment, Health, Housing, Income & Consumption, Jobs & Earnings, Knowledge & Skills, Time Use, Safety & Security, Social Connections, and Subjective Wellbeing.

• 4 Capital stocks that support wellbeing now and into the future: Natural Capital, Human Capital, Social Capital; Financial & Physical Capital

• Risk and resilience.

In New Zealand government, every ministry has to demonstrate their actions are increasing well-being and the 4 capital stocks that support well-being, prompting thinking about policy impacts and implications.

It complements rather than replaces the other analytical economic tools and frameworks that the Treasury uses, and that includes the budget.

To Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, the purpose of government spending is to ensure citizens’ health and life satisfaction, and that — not wealth or economic growth — is the metric by which a country’s progress should be measured.

In May 2019, New Zealand launched their first “Wellbeing Budget”, the first country to explicitly have well-being as its objective, a new standard for progressive policy. Initiatives targeting intergenerational well-being outcomes and expected impacts were presented and assessed against the Living Standards Framework well-being domains and capitals.

All spending must advance one of five government priorities, taken from evidence as the greatest opportunities to make real differences to the lives of New Zealanders:

• Taking Mental Health Seriously – Supporting mental well-being for all New Zealanders, with a special focus on under 24-year-olds

• Improving Child Wellbeing – Reducing child poverty and improving child well-being, including addressing family violence

• Supporting Māori and Pasifika Aspirations – Lifting Māori and Pacific incomes, skills and opportunities

• Building a Productive Nation – Supporting a thriving nation in the digital age through innovation, social and economic opportunities

• Transforming the Economy – Creating opportunities for productive businesses, regions, iwi and others to transition to a sustainable and low-emissions economy.

To measure progress to these goals, they will be tracked against 61 indicators, some novel such as loneliness and trust in government institutions, others more traditional like water quality.

Critics of the policy feel it ignores economy for the sake of branding and marketing, that it will set the country back financially. It also doesn’t include measures for many of the SDGs, such as climate, biodiversity protected areas, renewable energy, water quality and quantity, risk of poverty, and other issues such as waste recycling and crime.

The Living Standards Framework is a tool owned by the Treasury, rather than the wider New Zealand Government. Since it is neither a development strategy, nor a performance monitoring framework, it does not set specific goals or targets that unite government departments around a set of common objectives - an approach adopted in Scotland and Slovenia.

Some think that it’s a government’s job to look after the economy not individual happiness. But others would disagree,

“What is the purpose of government if it does not work toward the happiness of the people? It’s the duty and role of the government to create the right conditions for people to choose to be happy.” - Ohood bint Khalfan Roumi, Minister of State for Happiness and Well-Being, Bhutan, 2016.

New Zealand and Bhutan are among a small but growing group of countries taking steps to embed well-being more deeply and systematically into policy processes. Others using measurements of wellbeing of their people include Slovenia, Luxembourg, Korea, Australia, Italy, Israel, Belgium, Finland, UK, Germany.

Read more: