How to Measure Tourism’s Impact? Part 4: Rethinking Tourism Development - Doughnut Economics

/The Covid crisis shut down international tourism for 2-2.5 years and has inspired and catalysed creativity with the critical need to be resilient, sustainable, smarter and safer. It offers the opportunity to rethink how we do tourism, world-over, for planet, people and places.

Operationally even, we can't just go back to “Tourism As Usual”. So where do we go from here?

In Part 1, we asked, why and what’s wrong with tourism targeting quantity of visitors, not quality?

In Part 2, we considered whether tourism actually creates happiness, for hosts as well as guests, and how that can be measured ‘Beyond GDP’.

In Part 3, we looked at well-being, social progress and living standards, and measuring the impact of tourism within that context.

Now we’re rethinking tourism in the context of the newly re-opened world.

We simply cannot go back to the old ways, but need to reflect on why and how we engage with tourism. And in order to manage this, we still need to measure, but modes of measurement need to reflect our new purpose.

Historically, tourism accounting has measured inputs and KPI outputs, like visitors, income and profits. Now, we need to consider impacts and outcomes.

Tourism needs to deliver purpose, fairness and, as with every part of every sector globally, we encourage you to rethink your travel with in mind Agenda 2030’s sustainable development goals, and social planetary limits without being at the expense of people and places.

We Need to Change the Goal from GDP Growth

Welcome to Doughnut Economics

The Doughnut of social and planetary boundaries aims to “ensure that no one falls short on life’s essentials (from food and housing to healthcare and political voice), while ensuring that collectively we do not overshoot our pressure on Earth’s life-supporting systems, on which we fundamentally depend – such as a stable climate, fertile soils, and a protective ozone layer.” (Kate Raworth, 2017)

The Doughnut (2012) looks like this:

At the minimum living limits before falling into the doughnut ‘hole’ are the twelve dimensions of social foundation derived from internationally agreed minimum standards, as identified by the world’s governments in the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015 (energy, water, food, health, education, income & work, peace & justice, political voice, social equity, gender equality, housing, networks).

At the outer limit of the doughnut sit nine environmental planetary boundaries (freshwater withdrawals, land conversion, biodiversity loss, air pollution, ozone layer depletion, climate change, ocean acidification, chemical pollution, nitrogen and phosphorous loading - Rockstrom et al) overshooting beyond which lies unacceptable environmental degradation and potential tipping points in Earth systems.

In the dough in between the social foundation and the planetary boundaries lies an environmentally safe and socially just space in which humanity can thrive, where everyone’s needs and that of the planet are being met - a “breakthrough alternative to growth economics” (George Monbiot, journalist).

2. It’s Time to tell a New Story

How does Doughnut Economics apply to a Place?

In April 2020, Amsterdam announced it was embracing the Doughnut as a tool for transformative action to help the city recover from the economic mess caused by Covid-19 and to keep thriving in balance with the planet, and global responsibility and respect - the first city in the world to make such a commitment for public policy decisions (Guardian, 2020),

“Thriving means our wellbeing lies in balance. We know it so well in the level of our body. This is the moment we are going to connect bodily health to planetary health.” - Kate Raworth, 2020

The theory doesn’t specify targets to reach, rather it requires stakeholders to set appropriate benchmarks for the location.

Having measured the city against all the Doughnut’s inner and outer criteria, city managers were able to see clearly how issues interlink.

For example, with almost 20% of city tenants unable to cover their basic needs after paying rent, and just 12% of applicants for social housing being successful, more housing may be considered a priority.

But Amsterdam’s doughnut highlights carbon dioxide emissions 31% above 1990 levels, with 62% contributed by imports of building materials, food and consumer products from outside the city boundaries. The doughnut approach encourages policymakers therefore to consider bio based materials such as wood, to set new standards for circular use of materials in major works involving city-owned buildings (including a novel materials passport to enable their reuse) and aim to reduce food waste 50% by 2030.

Another campaign involved the construction of six new islands reclaimed from the sea using foundations that respect the local wildlife.

In tourism terms, Amsterdam was one of the first cities renowned for overtourism – an overshoot and imbalance of visitors creating a tipping point compromising residents’ homes, potentially cultural heritage and guest experience, satisfaction reviews and place/brand perception, upon which rests important city income: such indicators can thus be monitored and thresholds managed, and it facilitates us to see the bigger picture of tourism’s cross-sectoral impacts, on communities, landscapes and other ecosystems (Hartman & Heslinga, 2022).

The doughnut may not answer everything, but it highlights issues for questions and discussions, so ‘business as usual’ doesn’t not consider impacts and alternatives. It enables valuing things differently.

For example, it highlights Amsterdam as the world’s single largest importer of cocoa beans, mostly from West Africa, where the labour is often highly exploitative. And that almost one in five households in Amsterdam qualify for social benefits due to low incomes and savings.

3. We Need to Nurture Human Nature

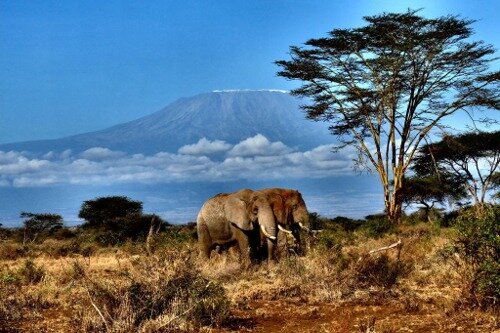

In tourism, it’s not just about cheapest prices, but emotional experiences. People genuinely want to ‘give back’ and support communities and conservation.

There are costs in daily lives not always reflected in capitalism: true costs, which should be reflected in true-pricing.

So Amsterdam is looking at this through the Doughnut lens, perhaps ironically/fittingly one of the first cities questioning the system as the original birthplace of the stock exchange with investment in the colonial Dutch East India Company: 20th century economic thinking is not equipped to deal with the 21st century reality of planet and resources on the edge of climate breakdown.

4. We Need to be Savvier with Systems Thinking

Tourism is a dynamic complex ecosystem integrated with many others: natural, economic, political, technical, local, regional, national and international. Every impact has ripple effects and implications.

Economic growth benefits don’t ‘trickle down’. We need distribution of wealth and benefits by design at the heart of economic policy.

Amsterdam is introducing massive infrastructure projects, employment schemes and new policies for government contracts.

Instead of growing GDP, should success equate to living a good life within the doughnut limits, like Amsterdam is aiming for its 872,000 residents?

5. We Need to Design to Distribute

Tourism needs to be designed for people and places to earn their fair share of benefits that the current system doesn’t enable. Local voices and values need to be prioritised.

Our take > make > waste linear economies have created degeneration: growth won’t clean things up. Circular economy of designing-out waste, reuse and regeneration of natural systems is required.

During lockdown, Amsterdam arranged collections of old and broken laptops from residents who could spare them, hired a firm to refurbish them and distributed 3,500 of them to residents in need, allowing them to access all kinds of social services during lockdowns and other emergencies while avoiding buying new and unnecessary e-waste.

Other cities experimenting with a Doughnut approach include Berlin, Brussels, Copenhagen, Dunedin (New Zealand), Melbourne, Nanaimo (Canada), Philadelphia and Portland (USA).

6. We Need to Create to Regenerate

We need to turn today’s economies from degenerative by default into regenerative by design: run on renewable energy and circular economy.

What does it mean for travel and tourism? Have we learnt lessons from the last years?

With Covid restrictions eased, will we now better value our trips away?

With climate, war and price inflation crises, will we see the ‘race to the bottom’ halted and true costs reflected?

Overtourism doesn’t benefit anyone. Amsterdam has now adopted a doughnut minimum of 10 million visitors and a maximum of 20 million visitors as emergency signals (limits), appointing 12 and 18 million visitors as early warning signals (thresholds) (Hartman and Heslinga, 2022).

7. We need to be Agostic about Growth

We don’t need more tourism. We need better tourism, for everyone.

We need to choose positive impact tourism where the aim is social and environmental goals, not business growth for its own sake.

We need to choose regeneration for the world.